|

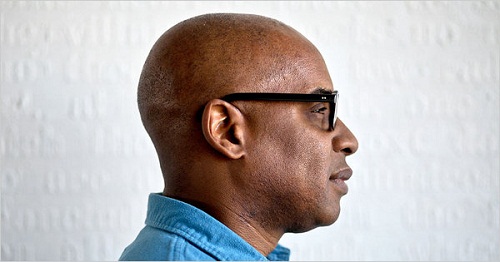

Fred R. Conrad/The New York Times |

Published: February 24, 2011

It’s the work of the New York Conceptual artist Glenn Ligon, whose midcareer retrospective, “Glenn Ligon: America,” opens at the Whitney on March 10. Taken from “Melanctha,” a 1909 novella by Gertrude Stein about a mixed-race woman, “negro sunshine” is the kind of ambiguous phrase that Mr. Ligon, who is black, uses to speak of the history of African-Americans. “I find her language fascinating,” he said of Stein. “It’s a phrase that stuck in my head.”

Are those two words, installed in such a prominent manner, meant to shock?

“Shock,” repeated Mr. Ligon, a bit surprised at the question. “It’s not provocative, it’s Gertrude Stein.”

“Even my Richard Pryor paintings,” he went on, referring to a series of work based on jokes told by that black comedian, use a common racial epithet. “Turn on the radio,” he said. “A word like that is so archaic, it’s not of this time. It’s about language.”

Since the late 1980s Mr. Ligon, 51, who is gay, has been creating paintings, prints and drawings using phrases written or uttered by personalities like Mary Shelley, James Baldwin and Malcolm X. Sometimes the words appear as a line floating in the middle of a canvas; other times are they are repeated over and over in a way that makes them abstract and illegible.

These phrases are often oblique — “I do not always feel colored”; “I lost my voice I found my voice”; “I was somebody”; “I am somebody” — raising a controversial or mysterious question and leaving the viewer to work for the answers. Mr. Ligon generally deals with race, gayness or simply what he calls “outsiderness,” and his paintings, drawings, sculptures and videos have captured the attention of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tate Modern in London and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, which all have his work in their permanent collections. He’s also been noticed by President and Mrs. Obama, who chose Mr. Ligon’s 1992 painting “Black Like Me #2” for their private quarters at the White House, on loan from the Hirshhorn.

“Glenn is someone who has figured out how to give Conceptualism some grit,” said Robert Storr, dean of the Yale School of Art, who bought an early painting by Mr. Ligon for himself and later another for MoMA when he was a curator there. “He’s influenced a younger generation, perhaps because he is a political artist but not a protest artist. He has an unwillingness to be boxed in.”

His retrospective feels particularly timely because it comes at a moment when glaring polemics are no longer fashionable. Artists these days raise social and historical issues but usually keep them at a distance. Yet the underlying messages of works like “Hands,” a photograph from the Million Man March, speak to the urgency of change. “His work captures political moments en masse, which seem quite compelling now when you consider the Middle East and the protests of collective bargaining in the Midwest as a form of democracy,” said the artist Lorna Simpson.

Since Mr. Ligon’s work draws heavily on written sources, one might expect his Brooklyn studio to resemble the Collyer Brothers’ apartment, a haphazard pile-up of books, magazines and papers. But instead, his sunny space is spotless, with only one neatly arranged bookshelf and crisp white walls where a few of his painting hang. (Others are carefully propped up on the floor, leaning against one another.)

On a recent wintry afternoon less than a month before the show Mr. Ligon greeted a visitor in a down jacket, apologizing because there was barely any heat in the building. When asked about his looming deadline, he could still manage his trademark throaty laugh. “I’ve become very Zen,” he said. “I’ve gone through all the stages: anger, bargaining, acceptance. These days I spend so much time at the Whitney, all the guards know me.”

Mr. Ligon is the kind of guy who could fit in anywhere. With his shaved head, black glasses and wide smile, he has an unassuming yet welcoming face, one that has appeared in J. Crew catalogs and Gap ads. He has a dry wit and can talk as easily about serious fiction as popular movies and television shows. “There was a time when I was a huge TV addict,” he confessed. “I used to race home from school to watch ‘Dark Shadows.’ ” More recently he has been hooked on the British soap opera “Downton Abbey,” which he enjoys partly because it’s about class.

Mr. Ligon himself grew up in a working-class family in the Bronx, his father a line foreman for General Motors and his mother a nurse’s aide. Weekdays he would commute to Manhattan, to Walden, a West Side private school, now defunct, where he and his older brother had scholarships. (“I don’t think my mother knew it was one of the most liberal schools in America,” he recalled.)

When he first thought he wanted to be an artist, his mother told him that “the only artists I ever heard of are dead,” but she enrolled him in pottery classes and made sure he got any book he wanted. “We didn’t have a lot of extra money, but there was an attitude that if it was educational, it was O.K.,” Mr. Ligon said. “Books, yes. Trips to the Met, yes. Hundred-dollar sneakers, no.” That, he said, may account for his love of literature. He reads voraciously — on paper, not on a screen — marking phrases that jump out at him.

Mr. Ligon went on to Wesleyan University with thoughts of becoming an architect, “but I realized I was more interested in how people live in buildings rather than making them,” he said. After college he became a proofreader in a law firm and painted at night and on weekends.

His big break came in 1989, when he got a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. “I thought if the government thinks I’m an artist, then I must be one,” he said. He started making art full time.

Now, although his studio is in Park Slope, he lives in Manhattan, near Chinatown. “I like having a studio to go to,” he said. “It’s like having a job.”

Although an urbanite at heart, Mr. Ligon also has a house in Hudson, N.Y., chosen for all the antiques shops and restaurants within walking distance. “In high school driver’s ed was at the same time as drama class,” he said, laughing. “And I had to take drama class. Now I can sing the lead in ‘Oklahoma!,’ but I can’t drive. ‘Oklahoma!’ was my destiny.”

So, it seems, is the Whitney. He joined its Independent Study Program in the mid-1980s and over the years has been part of many exhibitions, including two Biennials, the first in 1991 with three works for which he stenciled passages taken from the Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston on abandoned hollow-core doors. For the 1993 Biennial he produced an elaborate installation of photographs and texts examining the social implications of Robert Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic pictures of black men.

His work was also in the Whitney’s controversial “Black Male” exhibition the following year, where he showed a series of eight paintings in which newspaper profiles of the teenage black and Hispanic defendants in the Central Park jogger case were stenciled in oil stick on canvas. The results had the handmade look of early Jasper Johns, a hero of Mr. Ligon’s.

In 1996, when he had a show of drawings at the Brooklyn Museum, Holland Cotter, wrote in The New York Times: “Mr. Ligon’s drawn words have their own mystery. Seen through a haze of charcoal or in raking gallery light, they’re hard to read, but their ideas are big.”

Mr. Ligon slowly started gaining prominence in the early ’90s along with a generation of artists like Ms. Simpson, Gary Simmons and Janine Antoni. But he hit a kind of artistic jackpot when the Obamas chose “Black Like Me #2” for their private living space at the White House. It came as a total surprise to Mr. Ligon, who said he was “very flattered.”

“It’s not an easy piece, which is why I’m so thrilled,” said Mr. Ligon, who has never met the Obamas. The painting’s title echoes John Howard Griffin’s 1961 memoir, in which Griffin, who was white, traveled in the South posing as a black man.

In trying to capture the sweep of Mr. Ligon’s career, Scott Rothkopf, the Whitney curator who organized the retrospective, said he had tried to show him in a way that went beyond the obvious. “Although people think they know his work — the black and white text paintings in particular — I’ve tried to tease out the distinctions of one painting from another so that people can appreciate their specificity,” he said.

Mr. Ligon forms letters with stencils because “it’s a way to be semi-mechanical, to make letters that are not handwriting but have personality,” he said. “Handwriting would make these quotations too much mine, and stencils give it a bit more distance. They also allow me to keep being painterly but also have the kind of content I want a painting to have.” And rather than use oil paint, which can get messy, he uses oil stick, so that each letter has a more defined quality. For some works he has also flocked the canvas with coal dust to give it a textured, glittering feeling.

Neon sculptures create yet another message, a kind of 21st-century signage that hints at advertising but is quite the opposite of promotional. On the first floor of Mr. Ligon’s studio building is Lite Brite Neon, a custom lighting fabrication studio where, on a recent visit, the “negro sunshine” sculpture was being made for the Whitney’s window. On a long work table the perfectly made letters spelling out “negro” rested against a white metal backing.

As Mr. Ligon inspected the progress, he explained that the front of the letters will be painted black, for a shadow play between light and dark. In the show there will also be neon wall reliefs that spell out just one word — “America” — from which the retrospective’s title was taken.

Mr. Rothkopf said the decision to call the show “Glenn Ligon: America” was a very conscious one. “Although he emerged amidst a generation of artists who deal with race and sexual identity, his work speaks more broadly,” Mr. Rothkopf said. “Not just to African-Americans or gay Americans, but to all Americans.”

Even children. There will be work Mr. Ligon made in 2000, for an exhibition at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, where he gave kids black-history coloring books from the 1970s to crayon. What particularly fascinated him was how totally oblivious the children were to the political agenda behind the images. “One of the kids looked at the Malcom X picture and asked if it was me,” he said.

The retrospective will also include paintings based on “Stranger in the Village,” a 1953 essay by Baldwin. “I keep returning to it over and over again,” Mr. Ligon said. “It’s panoramic. Baldwin is in Switzerland, he’s working on a novel, and he’s thinking about what it means to be a stranger somewhere, literally and metaphorically. You have to be a bit outside of something to see it. I think any artist does that. It’s an artist’s job to always have their antennas up.”

Source link: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/27/arts/design/27ligon.html?_r=1

Interactive feature of Ligon's work: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2011/02/27/arts/design/20110227-ligon.html?ref=design

No comments:

Post a Comment