Celebrated Illustrator of Children’s Books, Is Dead at 79

Text | Margalit Fox for The New York Times, May 30, 2012

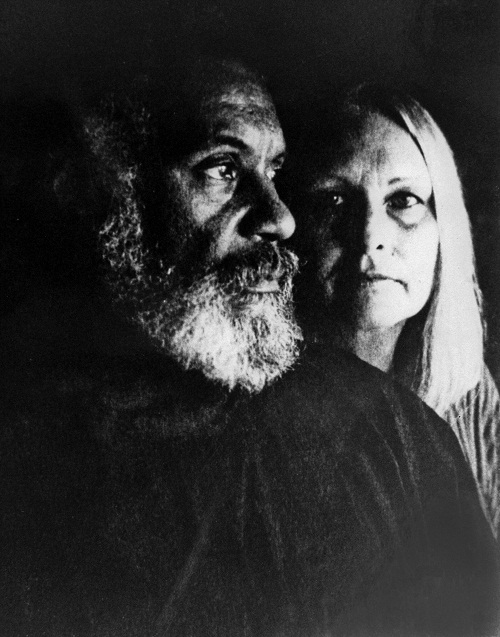

Leo Dillon, who with his wife and longtime collaborator, Diane, was one of the world’s pre-eminent illustrators for young people, producing artwork — praised for its vibrancy, ecumenicalism and sheer sumptuous beauty — that was a seamless amalgam of both their hands, died on May 26, 2012 in Brooklyn. He was 79.

The cause was complications of surgery for lung cancer, according to the Dillons’ publisher, Scholastic, which announced the death.

The Dillons, who met in art school, became instant archrivals and remained together from then on, won two Caldecott Medals, considered the nation’s highest honor for children’s-book illustration.

The first, in 1976, was for “Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears,” a West African folk tale retold by Verna Aardema; the second, in 1977, was for “Ashanti to Zulu: African Traditions,” by Margaret Musgrove.

Mr. Dillon was the first African-American to receive the Caldecott; the couple remain the only illustrators to have won it two years in a row.

The dozens of books for children and adults illustrated by the Dillons include titles by Ray Bradbury, Virginia Hamilton, P. L. Travers and the soprano Leontyne Price, whose 1990 picture-book adaptation of Verdi’s “Aida” was praised for its Egyptian- and African-inspired artwork.

Though artistic teams have long collaborated on illustrated books, it is far more common for one partner to furnish the text and the other the pictures. It is far less common for both to make the art in tandem, as did the Dillons, who began their career jointly illustrating album covers and jackets for adult science-fiction books.

Their modus operandi, honed over time, involved an initial discussion — a negotiation, to hear them tell it — of their visions of the text. When these were more or less reconciled, one of them made preliminary sketches, which were passed to the other for coloring, then passed back for refinement.

After sufficient back-and-forth, and sufficient spirited argument, the resulting image appeared, they often said, to have been the work of an unseen but very much present third party, whom they called “It.”

The Dillons’ work was characterized by stylistic diversity, with influences ranging over African folk art, Japanese woodcuts, old-master paintings and medieval illumination.

It was also noteworthy for the diversity of the people it portrayed. This was especially striking in the 1970s, when the Dillons began illustrating for children: until then, the smiling faces portrayed in picture books had been overwhelmingly white.

Their emphasis on inclusion sprang from their experience as an interracial couple. As they often explained in interviews, after their son, Lee, was born in the 1960s, they surreptitiously colored the skin of characters in the picture books they bought him, recasting them as black, Hispanic and Asian.

The son of parents who had come to the United States from Trinidad, Lionel John Dillon Jr. was born in the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn on March 2, 1933.

As a high school student, he was groomed for a career in commercial art. But his gifts were spotted by a teacher who realized, as Mr. Dillon later said, “that I could do more than illustrate Coke bottles” and steered him toward fine art.

He enlisted in the Navy so that he could attend art school afterward on the G.I. Bill. After three years’ service, he enrolled at the Parsons School of Design in New York.

Viewing an exhibition of student work there one day, Mr. Dillon was captivated by a still life of an Eames chair.

“I knew it had to be by a new student because nobody in our class at the time could paint like that,” he told The Horn Book, a magazine about children’s literature. “This artist was a whole lot better than I. I figured I’d better find out who he was.”

“He” turned out to be Diane Claire Sorber, and a crackling competition ensued. “If one got a better place in a show, we wouldn’t speak for three weeks,” Ms. Dillon told The Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1990.

In the end, the only thing for it was marriage, which, she said, “was a survival mechanism to keep us from killing each other.”

The couple, who graduated in 1956, were wed the next year, and “It” was born soon afterward.

Their other books include “Two Pairs of Shoes” (1980), Travers’s retelling of two Middle Eastern folk tales; “The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales” (1985), retold by Ms. Hamilton; “Pish, Posh, Said Hieronymus Bosch” (1991), by Nancy Willard; “To Every Thing There Is a Season” (1998), drawn from Ecclesiastes; and two titles for which they also wrote the text, “Rap a Tap Tap: Here’s Bojangles — Think of That!” (2002) and “Jazz on a Saturday Night” (2007).

Their work has been the subject of museum exhibitions and a book, “The Art of Leo & Diane Dillon” (1981), edited by Byron Preiss.

A picture book written and illustrated by the Dillons, “If Kids Ran the World,” is scheduled to be published by Blue Sky Press, a Scholastic imprint, in 2014.

Mr. Dillon, who lived in the Cobble Hill section of Brooklyn, is survived by his son, Lee, a sculptor and studio jeweler.

Also surviving is his wife, Diane Dillon, half of the presence that animates “It.”

No comments:

Post a Comment